I question the notion of a pure Bahamian identity

Forging A 'Caribbean Connection'

By NOELLE NICOLLS

Tribune Features Editor

nnicolls@tribunemedia.net

Nassau, The Bahamas

LAST month the Bahamas National Youth Council, a non-profit organization representing youth voices in the country, commemorated Caribbean Youth Day with a youth march and forum. President of the council Tye McKenzie publicly associated himself with rational and bold albeit unpopular positions on Caribbean integration and I salute him for doing so. It made me think, regionalism is not dead in the Bahamas after all: It was a thought that gave me hope. In fact, it inspired me, as a fellow advocate of regional integration.

But it also made me think: How unfortunate that supporting a simple idea such as proudly affirming a Caribbean identity, and the “beckoning reality of integration and corporate development as a region” would be a bold action in this age of collapsing borders and social networking.

Caribbean people today are probably more integrated than in any other time in our history. And yet, today, anti-integration sentiments still hold major political currency, and it still seems rationale to assert that regional integration is irrelevant.

In the case of The Bahamas, we continue to resist the idea that the Haitian presence is not in fact anti-Bahamian, but is quintessentially Bahamian. Illegal immigration clouds the consciousness, but in reality, the two nations have always shared a close economic and cultural relationship, not to mention that familial ties are deeply entrenched in the Bahamian identity.

Illegal immigration also creates the false perception that people in the wider Caribbean hate their countries and see The Bahamas or their chosen destination as the Promised Land, which could be nothing further from the truth; and the false perception that immigrants are somehow inferior, low-grade, even depraved human specimens, which of course, is not only untrue, but highly ignorant.

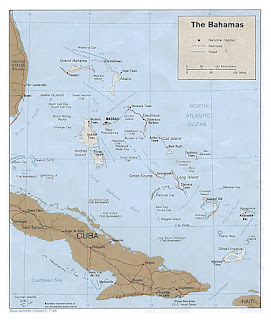

We have yet to come to terms with the simple idea that our relationship with the United States of America, particularly our historical connections to the Carolinas and South Florida, does not negate our connection to the Caribbean region. Our geography has always placed us in a unique cross-border position: American and Caribbean; Western and Colonial; influential and inconsequential, sprawling and diminutive. For these and many other reasons we “exude the essence of a liminal existence”, as cultural scholar Dr Jahlani Niaah has observed in the past.

A large population of our political and business class were educated in regional institutions and in their private lives many of them manifest the essence of regionalism. Their contemporary politics would not suggest so because it has called for them to virtually rebel against their own upbringing. And in doing so, they have led a subliminal disintegration movement with a pervasive effect on public consciousness.

In almost every sphere of Bahamian society – politics, education, the public service, civil society, and business – Bahamians with Caribbean heritage are and have been leading figures. The Bahamas’ fledging police and defence forces were riddled with Caribbean nationals; so too was the teaching and nursing professions. This was not a mark of Bahamian inferiority. It reflected population dynamics and a Caribbean reality, which was later made problematic for political expediency due to evolving socio-economic and geopolitical realties.

Politics aside, The Bahamas has always been integrated. The current governor general Sir Arthur Foulkes is of Haitian heritage. Junkanoo Queen and cultural pioneer Maureen “Bahama Mama” Duvalier was also of Haitian ancestry. The Maynard political dynasty is of Bajan heritage. Beloved Canon Neil Roach was himself born in Trinidad and Tobago. Paul Thompson, a well-respected former assistant commissioner of police was also born in Trinidad. The first black man to sit in The Bahamas House of Assembly was Stephen Dillette of Haitian ancestry. And the first black man to lead the nation, Sir Lynden Pindling, was of Jamaican heritage.

Given the level of integration present at all levels of our society, historically and contemporarily, I question the notion of a pure Bahamian identity, and the political motivations of those who promote such a concept.

In the mid-1900s, the United Bahamian Party (UBP) distributed pamphlets, considered promotional tourism paraphernalia, which asserted that the Bahamas was not in the Caribbean, but in the Atlantic Ocean. The government actively waged a propaganda war against any notion of a Caribbean identity.

Their tactics, motivated by economic and political realities, are not to be confused with an enlightened awareness as to whom we were as a people. In fact, the UBP’s capacity to envision an identity for the Bahamian people is to be seriously questioned, considering it excluded true consideration for the vast majority of the Bahamian people.

The Caribbean connection, while existing partly because of the similar colonial structures that were established across the islands, derives its true source of origin and power from the anthropological connections that exist amongst formerly enslaved Africans and their descendants scattered across the islands. The latter is at the heart of the Caribbean connection, and they manifest in tangible ways through our food, language, dance, music, art, literature, philosophy, rituals, ancestry, spirituality and other traditions. So in one way, it is to be understood, why such a connection could not have been or would not have been appreciated in an era of UBP politics.

What I cannot understand is why such a connection is not fully appreciated today. What I cannot understand is why our leaders do not cut the crap and affirm our Caribbean identity. What I cannot understand is why we continue to deny our Caribbean identity with farcical arguments usually linked to some notion of the Caribbean Sea and our exclusion from that body of water.

Arguably, the Caribbean Sea, although a convenient signifier, is one of the most insignificant measures to mark the Caribbean identity. Its name is derived from the French articulation “Mer des Antilles” or Sea of the Antilles. Before European nations happened upon the New World, their medieval navigational charts demarked a mysterious set of lands between the Canary Islands and India as Antilia. The name was appropriated by the French, Spanish, Dutch and German colonizers to identify specific sets of islands colonized in the West Indies. Antilles in English became synonymous with Caribbean or West Indies. And the body of water internally bordered by Antilles islands became known as the Caribbean Sea.

The Bahamas, although part of the West Indies, was never generally included in the Antillean islands. And, of course, the Bahamas does not border the Caribbean Sea. None of these facts support the denial of the Bahamas’ Caribbean identity. The Caribbean Sea, while geographically significant, has never been a core galvanizing concept for the Caribbean.

The most obvious eventualities, as well as the most enlightened possibilities, are sometimes the most daunting, so instead of boldly stepping into the future and proactively charting a course, we too often play it small, absorbing ourselves in parochial concerns and narrow visions.

This is a fundamental challenge of leadership: balancing the often competing interests of immediate concerns and future possibilities; of safe ideas and big visions. As a Bahamian I exist inside a world of 300,000 plus people. As a Caribbean national I exist inside a world of 39 million people. As a global citizen I exist inside a world of seven billion.

Some are daunted by this perspective, while some are exhilarated. There will be those who feel safe and secure within the confines of the Bahamian bubble. Because, truth be told, many people profit greatly inside the bubble, as well as, many people feel completely inadequate outside.

Regardless, however, should not the possibility of a bigger existence be available to Bahamians: A world where those who choose to play it small are free to do so and those who choose to play it large are equally free to do so?

In the age of technology the Caribbean, indeed the world, is closer than ever before, and still our leaders continue with such parochial ways of thinking. Yes, there are nationalistic endeavours to be pursued, but not to the exclusion of a way of thinking that embraces our integrated identities and cross border relationships. Our leaders are supposed to help us to dream bigger and “dream better”, but it often seems they are intent on making us smaller and smaller, no doubt to affirm their own sense of superiority and to affirm their own relevance.

I am reminded of the famous quote by Marianne Williamson, made popular by Nelson Mandela, which I believe is worth quoting in its entirety: “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, and fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small doesn’t serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won’t feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. We are born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. It is not just in some of us; it is in everyone. And as we let our light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others.”

The Jamaican saying “we likkle but we tallawah” is an expression of the power and the capacity for greatness that Ms Williamson alludes to. To their credit, the achievements of Jamaicans continue to be proof positive of the claim: from Marcus Garvey to Bob Marley to Usain Bolt. Jamaicans for nationalistic reasons claim this power as exclusive to themselves, but in truth, it describes a classic Caribbean spirit. Not the element of exceptionalism, which we see countries around the world embracing, the United States most notoriously. It is the element of being so small yet having the capacity for such greatness; of being so inconsequential and yet so influential. And all Caribbean countries can boast of this existence.

Ask Haiti, which started the trend with the Haitian Revolution. Ask Cuba, which will continue to affirm this reality every day the Americans maintain its unconscionable blockade. Ask Grenada, which felt its global significance at the hands of American military might. Ask the Eastern Caribbean nations whose agricultural production spurred a fierce global trade war between European nations and the United States.

In the past two years, two Caribbean countries leaped far ahead of the global curve in electing female heads of states: Prime Minister Portia Simpson Miller in Jamaica and Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar in Trinidad and Tobago.

And the Bahamas after all, for all of its global insignificance, has had five million tourists visit its shores in one year. And despite Jamaica’s athletic prowess, in the past three decades, the Bahamas has been in the top three of top medal earners in the per capita medal count for the Olympics. For five non-consecutive Olympic Games, the Bahamas was number one in the world in this ranking.

So what more could the Caribbean make of all this greatness, of all this significant insignificance? What more could we make by harnessing our collective power and imagination? And what more could we do if we toned down the exceptionalism and embraced the collectivism?

No doubt the light we could shine on the world would be intimidating for some, audacious even. And so what.

I proudly affirm my Caribbean identity and that of the Bahamas. I am encouraged that there are other young voices out there that are courageous enough to do the same. Too often I am disappointed by youth organizations or youth leaders who merely mimic the rhetoric and behaviour of the established leadership. Such was my great disappointment in the last general election, which was billed as the election to mark the great transition from the old guard to the new generation. Well through my eyes the new crop sounded just as antiquated as the old.

I truly wish a new wave of thinking could just sweep over our politics and bring bold visions to our people. The West Indies Cricket team won the Cricket World Cup last week. Imagine the scale of world dominance if we competed in the Olympics as a regional block, if only in a symbolic way with CARICOM uniforms creatively designating our nation states. What a statement to the world.

But such an achievement would sadly require us to do something that our political leaders have for the most part been incapable of doing. Sacrificing the ego-driven urge to want to be in control and to feel exceptional; sacrificing for a greater good, which is the harnessing our collective power.

That task is not impossible and some of us are up to the challenge. And the reality is we have evolution on our side. The Caribbean is integrated and is further integrating day by day. Technological advances have accelerated the process. It is mainly our politics holding us back. A kind of politics that insists on being reactive and not proactive.

At a recent regional meeting held in the Bahamas, the 21st annual conference of the Caribbean Water and Wastewater Association, one participant reported great success amongst delegates from the perspective of finding common ground in the discussed concerns and solutions. However, as it concerned the last-day meeting of ten regional ministerial heads, he predicted, “you will have to cut through the testosterone to get to your seat”.

Caribbean people are making headway where Caribbean governments have shown incompetence, inertia, a lack of will or an impoverished capacity to lead.

Anyone who claims there is no Caribbean identity and worse that there is no value in the Caribbean identity is on the wrong side of evolution and progress. Caribbean integration is not a failed experiment and it should not be abandoned by our leadership. It must assume a higher degree of importance, as it is a vital source of cultural and economic empowerment, and global significance. It is up to us to determine what we make of the infinite possibilities. And it begins with the simple embrace and affirmation of who we are.

October 15, 2012

Tribune 242